For almost two decades now, I have had a Fabian Society pamphlet society pamphlet sat on my bookshelf with the title ‘2025: What next for the Make Poverty History generation?‘ Having finally arrived at the mentioned year, I thought I would take a look and see how well the predictions mapped out to the reality.

There is a point to all of this. One of the things I often notice in old media is that at no point in time does society ever seem to actually be less worried about things. Certainly, when we look back we can see times as being more innocent or peaceful, but we do so with the knowledge that things actually turned out okay, we never remember the anxiety we felt at the time looking ahead to the future.

While the anxiety may be constant, the subject of that anxiety seems to constantly change. Having listened to all of the BBC’s publicly available archive of Alistair Cooke’s Letter from America back to the late 40s, decade by decade you are walked through the latest issues of obsession for politicians, journalists and the public only to find that they disappear into nothingness with the passage of time.

I think that there’s a certain amount of hope to be found in all of this, that while we should take the issues we face seriously, every generation thought they were standing on the brink of catastrophes which in the end never came to pass.

Despite this, in reading 2025, the greater surprise was the level of optimism to be found in its pages. A real belief that things were going well and that things would continue to improve over time, particularly in working to build a world which was more free: free from poverty, free from international debt choking off less developed economies, free from deaths from preventable or treatable diseases.

It envisaged a world in which the UK had strong and growing international status and was capable of playing a major role in leading the world into this future. Given the country’s self-inflicted harm over the years since, it made for painful reading.

It would be easy to dismiss the optimistic tone as the result of it being the work of a Labour-aligned thinktank a year into the party’s first ever third consecutive term in Government, but when you look back 2006 was a far more optimistic time in general. The impact of the 2008 financial crisis and the huge economic mistakes make in the UK since 2010 have robbed people of more than money alone, it stole people’s hope in a better future, and to be fair to the pamphlet, it did actually get this right in its section on scenario-planning.

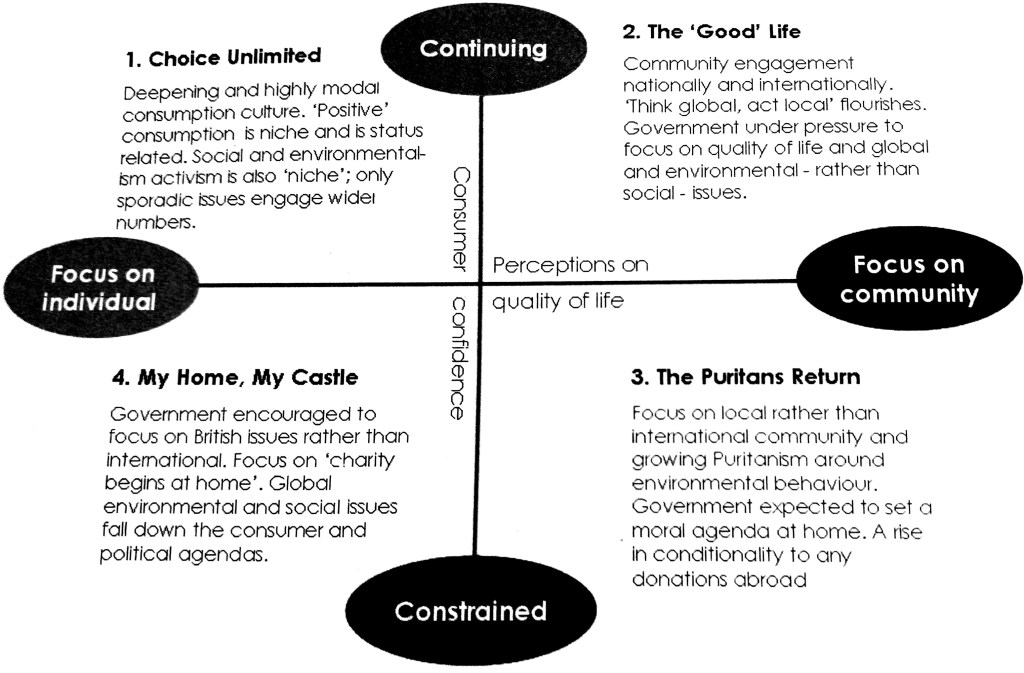

Instead of trying to predict the most likely version of the future, scenario-planning looks at the factors which could determine what the future looks like and then tries to create scenarios for what each combination of those factors would look like.

Scenario-planning has largely been used by companies to work out how to position themselves in a way where they can succeed in any of the scenarios predicted and it first came to prominence when Shell, who largely developed the approach, became the only company to profit out of the 1973 Oil Crisis.

It is unusual to apply scenario-planning to social issues, but not unheard of. I encountered it in my first job after university, working at University College London’s Constitution Unit while they attempted, with mixed success, to see how the UK’s constitution might evolve over the following decade.

In this case, they applied a simple model consisting of two axes.

It seems fairly clear that when you compare the 2006 heyday to much of the last 19 years, consumer confidence has clearly been constrained. The ‘perceptions on quality of life’ factor, whether people’s sense on the ‘good life’ focuses on themselves or the wider community, is much harder to gauge.

Results from the British Values Survey over the last 19 years has shown movement in both directions over this period, although with government policy over much of that period generally prioritising ‘individual’ over ‘community’, the reality is that we’re probably looking at a mixture of the ‘My Home, My Castle’ scenario and ‘The Puritans Return’, although with a greater component of the former.

So, in scenario-planning at least, the pamphlet does seem to have captured some insight into where things might have ended up around global issues in the UK by the time the world hit 2025, even if the predictions didn’t come close to the reality for the most part. Still, at least at least the premise wasn’t off, certainly when compared to the pamphlet considering what the world would be like once China became world’s dominant economy…in 2020.

Discover more from Peter Lamb for Crawley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.