Today is the International Day of Democracy, a day to celebrate the principles of democracy and to reflect on the state of democracy around the world.

While the evolving nature of the British constitution and the gradual expansion of the electoral franchise means that the exact point at which the UK became a democracy is open to debate, that doesn’t detract from the fact that we live in one of the oldest democracies in the world and the home of the mother of parliaments.

Unfortunately, while having an uncodified constitution has allowed the UK to gradually evolve into a democracy, it also leaves the UK’s democratic structures highly vulnerable to the whims of the government of the day. Really there are only three safeguards: the willigness of those in government to abide by long-established democratic conventions, the willingness of the public and civil society to defend those conventions, and the ability of the European Court of Human Rights to hold up a mirror to the actions of its member states.

The first two of these safeguards have been tested to their limits over recent years, as ministers have first sought to subvert established parliamentary traditions in order to secure political goals, only to find that their actions reinforced rather than condemned by civic society.

The last of these protections, the European Court of Human Rights has been under sustained attack now ever since the UK started to lose decisions back in the 1980s, periodically gaining new energy on the right-wing of the Conservative Party. It’s also not even remotely what most people think it is.

The European Court of Human Rights comes out of the European Convention on Human Rights, it has nothing to do with the European Union and in fact pre-dates the Treaty of Rome by some seven years.

After the horrors of the Second World War it was thought that it might be a good idea to ensure that every European country had at least some basic system of protecting people’s human rights, so the Allied powers wrote a convention setting out commonly held notions of what basic protections people were entitled to. Much of this work was undertaken by British lawyers, creating for the first time a comprehensive account of British legal and political traditions with regard to people’s rights.

Were these rights unreasonable? Well, that’s up to you to decide really, and you can either have a read through and make your mind up yourself (it’s really not very long) or watch a funny video about it starring Patrick Stewart.

Following the convention, the court was set up so that where the rights stated in the convention may well have been broken, an individual has the power to appeal that decision. Unlike most courts, it doesn’t actually have the power to correct a human rights abuse committed by a government, but it does hold up a mirror up to abuses of human rights by member states and the shame is usually enough to make a country think again.

From the 1980s, the UK started losing cases, as under Margaret Thatcher the UK started to depart from many of these long-established notions of British liberty, so Conservative MPs started to attack the convention as an abuse of British sovereignty even though it held no direct power over government decision-making.

To try to resolve some of these issues in 1998 Labour introduced the Human Rights Act, bringing the convention onto the UK statute book for the first time (it’s not a copy-paste job, the law literally refers to sections of the convention forming part of the act, without the convention the Act doesn’t exist). This had two effects. The first is that it meant people didn’t have to go all the way to the European Court to get a ruling on potential human rights abuses. The second is that it set up safeguards in the legislative process to catch where new laws have the potential to breach of the convention, so that there’s time to rethink them before they ever take place.

It was a clever way of bringing human rights law onto the statute book in a way which should protect people’s rights but without binding Parliament’s hands. Unfortunately, much like the rest of the constitution, it relies upon governments behaving honorably or at least being too scared of civic society to step outside of our democractic safeguards, and without those two elements the only protection left is for an external body such as the European Court of Human Rights to hold up a mirror to our indecency.

I have long been a fan of the UK’s uncodified constitution, my Master’s dissertation looked at one aspect of it and my first job ourside of university was undertaking research at UCL’s Constitution Unit. The way that it could evolve to new challenges seemed elegant and more open to democratic change than states with fully written constitutions. Unfortunately, three years of Boris Johnson was enough to break this conviction.

It is clear that a democratic system cannot survive when a Government is prepared to constantly lie, break centuries’ long parliamentary conventions, and place undue influence upon the independent safeguards designed to protect the foundations of our democracy, an uncodified constitution effectively ceases to exist.

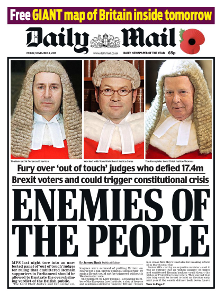

So, on the International Day of Democracy we are confronted with a government which has repeatedly changed the rules around voter registration and voting processes to try to eliminate those groups least likely to vote for them, where fixed-term parliaments are introduced and dropped whenever it is politically beneficial for the Conservative Party, where basic rights to protest and freedoms of speech are curtailed, where judges and civil servants are actively intimidated in undertaking the course of their jobs, where the Monarch is lied to in order to deprive people’s elected representatives in Parliament the ability to scrutinise the activities of government. Here in the land of the mother of parliaments.

It is a national disgrace. Unfortunately, much like in the USA where even now supporters of a major political party are happy to support a president who supported armed insurrection against his own country, there will be those in the UK who continue to defend these actions.

Why not? They’ve always supported that party and so did their parents. It’s a part of their identity. It’s their team no matter what they do. The other lot must be just as bad. Every excuse under the sun, as the UK heads towards oligarchy.

Discover more from Peter Lamb for Crawley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.